Today, methods for computational fluid dynamics (CFD) are widely covered in textbooks and are commonly used in many areas of engineering. These methods are helpful for designing and building systems in fields like turbo machinery, aerospace, and others. In this paper, we look at how CFD is used in microfluidic devices and some of the specific challenges that come with working on such a small scale, thus the reason many turn to CFD software.

In microfluidic systems, surface forces become more important than body forces. This requires special attention when dealing with problems that involve two-phase flows and free surfaces, which are often influenced by capillary forces. Common examples include capillary action or droplet formation. These flows usually happen at low Weber and Reynolds numbers. To model flows that include surface tension effects, the volume-of-fluid (VOF) method has been developed and continues to be improved.

Another important factor in microfluidics is the role of diffusion in mixing fluids. Since the Reynolds numbers are very low in microfluidic flows, turbulence rarely occurs, and mixing relies only on diffusion at low Peclet numbers. To achieve fast mixing, it is necessary to shorten the diffusion path of the fluids. This can be done using techniques like multilayered flows or creating chaotic motion in the fluid. While the lack of turbulence makes CFD modeling simpler in some ways, accurately modeling diffusion is still a challenge. To reduce numerical errors known as “numerical diffusion,” higher-order calculation methods are needed.

Both free surface effects and diffusion have been studied extensively in CFD literature from a technical standpoint. There are several ways to simulate these problems in different situations and with varying levels of accuracy. In this paper, however, we take a practical view. We ask: How useful are existing CFD software tools for engineers working with microfluidics?

Since these problems cannot be solved using formulas alone, they must be tackled using numerical methods like CFD. The key questions are whether these tools are available and how well they work for engineers. To answer this, we carried out a case study using several commercial CFD software tools and compared the results to experiments when available. Because there are many CFD tools on the market and limited time and resources, we chose to focus on four popular finite volume codes. Comparing them with well-known finite element tools like COVENTOR or COMSOL was beyond the scope of this work.

Benchmarking is an important part of CFD research and helps in checking and improving software accuracy. However, because the software used here is commercial, their internal workings are not publicly known. As a result, this study can only describe what the tools did in the test cases. It cannot fully explain why they behaved the way they did. Still, the results give a good idea of what CFD can currently do in microfluidics and which tools are best suited for certain tasks.

The devices tested were chosen based on real problems the authors encountered in past research, not to push the tools to their limits. Much of the paper focuses on using simulation methods for microfluidic devices that have not been discussed in previous papers. We hope the results will help engineers using CFD and also support software developers looking to improve their CFD tools.

Approach

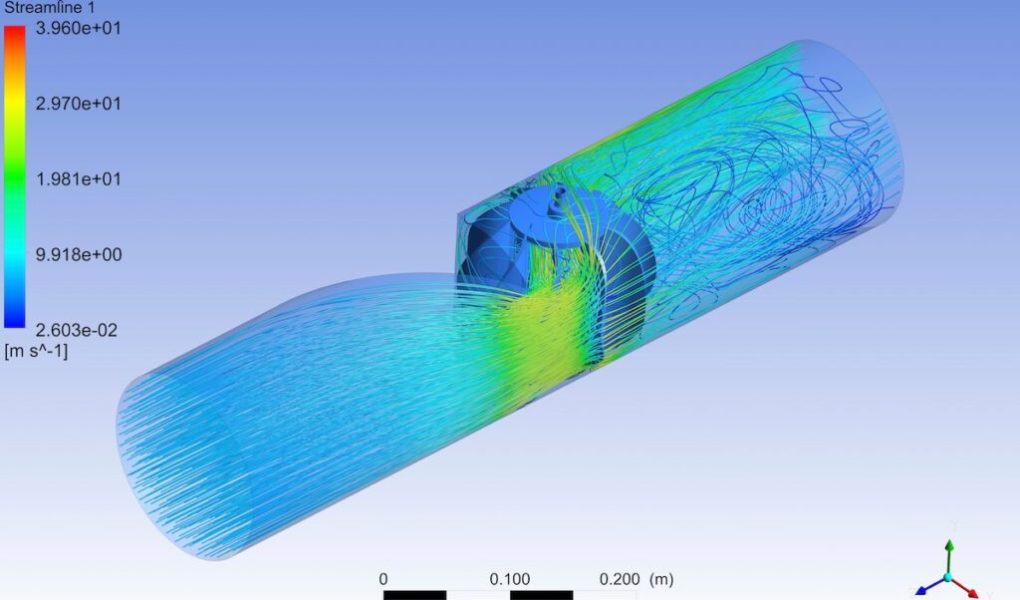

This paper looks at a few typical microfluidic problems to assess how well different simulation tools perform. The chosen problems focus on two key features: mixing at low Reynolds numbers and flows affected by surface tension. Each of the four problems, described in detail in Section 4, was simulated using the four CFD codes introduced in Section 3.

Software and Hardware Description

The case study uses the following software tools: CFD-ACE+, CFX, FLOW-3D, and FLUENT. All except FLOW-3D are based on the finite volume method for solving the Navier–Stokes equations. FLOW-3D uses both finite difference and finite volume approaches and applies a control volume method for solving conservation equations. Most of the tools use the SimpleC method for coupling velocity and pressure.

Simulations and Results

All simulations were done using structured grids, as mentioned earlier. Transient simulations used a first-order Euler method with fixed time steps, except for FLOW-3D, which required automatic time step control. The VOF method was used in all tools. However, CFX applied a high-resolution scheme using an implicit second-order Euler method.

Computational Speed

The speed results discussed here reflect how the software tools performed with the specific test problems. It is worth noting that each software could likely run the problems faster under different settings. Using a structured grid and fixed time steps is not the best setup for maximizing speed in these tools.

Conclusions

The results show that all tools performed well in solving convection-diffusion problems using a second-order method for tracing the flow. The level of numerical diffusion was low and similar across the tools, making them suitable for analyzing flow patterns and mixing in microfluidic devices. However, because experimental data was limited, a full comparison between simulation and reality was not possible in this study.